You could soon have a digital twin of yourself

Most of us are aware of the digital twins used in factories and industrial sites – but human beings could have digital versions of themselves, too.

Illustration: Nadia Méndez/WIRED Middle East

Imagine living in a world where a virtual replica of yourself mirrors your physical and psychological traits, constantly learning and evolving alongside you. A replica created using the data collected from sensors, medical records, and the wearable tech that accompanies you everywhere. This isn’t the stuff of science fiction, it’s the cutting–edge realm of human digital twins.

How far away from such a reality are we? Reasonably far. Academic and industrial communities are still in the early stages of exploring human digital twins, although a full digital twin of a human being could be possible within the next decade. The logical evolution of wearable health tech, these virtual replicas could transform healthcare, providing round–the–clock, personalized health management and alerting doctors to possible health risks in advance.

“Currently, most research institutions are focusing on creating digital twins of specific body parts or organs, such as heart digital twins and brain digital twins,” says Chenyu Tang, a second-year PhD student at Occhipinti Group, Department of Engineering, University of Cambridge. “Establishing a complete human digital twin is still a long way off. Compared to industrial systems, the core challenge in creating a human digital twin lies in the more complex and uncertain information patterns inherent in the human body. To achieve successful modeling similar to industrial systems, we need more advanced sensor technology to accurately monitor these information patterns and more advanced artificial intelligence technology to effectively analyze them.”

One company that is creating digital twins of specific organs is IT and consulting firm Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), which announced last October that it was creating the first-ever digital heart, that of the long-distance runner Des Linden. Based on an MRI of Linden’s heart, which provides the essential data needed to model the heart virtually, the twin will provide precise data on the heart’s function, efficiency, and response to varying conditions. It will also allow researchers to investigate the myocardium and subcellular mechanisms of a human heart, as well as its electromechanical activation (the generation and conduction of cardiac electrical potential leading to cardiac muscle contraction), and hemodynamics (the valvular functions, chamber pressures, myocardial wall tension, and coronary blood flow within the heart).

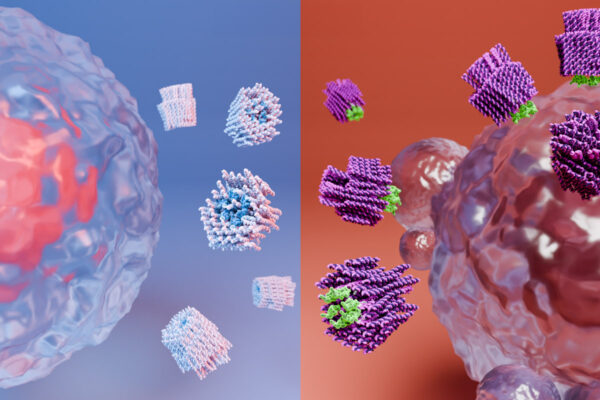

“While digital twins are a mature use-case in manufacturing, their use within healthcare and life sciences is nascent,” says Frank Diana, principal futurist at TCS. “However, with TCS’s work to innovate Digital BioTwins, and the successful digital heart model we have created with long-distance runner Des Linden, we are on the path to creating full digital twins of human beings. Already, Digital BioTwins are being used in research labs to test new drug formulations and more.” TCS’s Digital BioTwins initiative seeks to create digital replicas of biological entities such as organs, systems, or entire organisms.

Using AI-powered digital twin technology, the first-ever digital heart was created to power and optimize long-distance runner Des Linden’s training plan with data-driven insights based on health and performance. Courtesy of TCS

As Tang notes, however, creating a full human digital twin is something else altogether. The immune system alone is inherently complex, with its multifaceted structure, numerous cell types, and intricate regulatory mechanisms. This throws up innumerable challenges, not least access to the right types and scale of data, says Diana. “Modelling at the cellular level can be accomplished, but it will require new mechanisms to gather accurate data,” he states. “Nanobots, a developing technology which will provide huge utility in healthcare in the future, may hold the answer. Nanobots could be deployed inside a human orally or by injection to a specific site. The nanobots would be designed to collect data at the deeper levels required to model a full human.” Diana also suggests that, from a data analytics and ‘what if’ modeling perspective, AI will provide considerable and rapid advancements in our understanding of the complexities of the human body. It will also improve the accuracy of predictive modeling of the body over time.

There are concerns, of course, not least the reliability of models and the potential for incorrect or harmful recommendations to be made based on inaccurate data, says Tang. One of the authors of ‘A roadmap for the development of human body digital twins’, which was published in February, he also highlights concerns that have plagued the development of other technologies, including AI and autonomous vehicles: data security and ethical issues.

“Ensuring the secure and private flow of data between users, databases, and doctors is crucial for the practical use of human digital twins,” says Tang, whose co-authors include Wentian Yi and Luigi Occhipinti. “Additionally, developing sensors capable of continuously monitoring more complex information patterns and corresponding AI analysis technologies are significant technical challenges in establishing human digital twins.”

Security and privacy are a concern for Diana, too, who notes that the risks of developing digital twins are similar to those confronted by any technology relying on data faces. “To be accurate and truly effective, digital twins must access large amounts of data over time,” he explains. “This data could be vulnerable to cyber–attacks if it is not safeguarded correctly. In addition, as we are seeing with AI, it is likely that digital twins may need their own set of regulations to ensure ethical use of personal data and that confidential information is kept private.”

Last year, two assistant professors from the University of Central Florida – Luis Favela and Mary Jean Amon – claimed that human digital twins have the potential to facilitate human rights violations and “encroach into features that constitute a human’s personhood”. Such concerns raise “pressing issues of consent and violations of privacy rights”, they wrote. Numerous other ethical questions will arise as the technology nears reality. “For instance, should a parent be able to ‘speak’ to a digital twin of their deceased child?” asks Diana. “This could be cathartic, but could it be traumatizing? When I present this question to audiences at conferences or on social media, I receive a range of answers. These types of questions are challenging but will need to be asked and answered as the technology advances.”

If the issues of security, privacy, and ethics can be addressed successfully, the potential for human digital twins to revolutionize healthcare is considerable. They will help doctors identify future risks, enable remote care, and dramatically improve the identification and diagnosis of diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. Patients could receive comprehensive health analyses without leaving their homes and seamlessly share their health status with doctors, says Tang, just as doctors could better plan medical intervention by modeling and anticipating the effect of surgeries, therapies and other treatments.

“Human digital twins offer the potential to provide remote, real-time interactive, and easily understandable analyses of human health,” says Tang, who along with his co-authors has proposed a five-level roadmap to guide their development. This roadmap includes real-time assessment of a person’s physical state using AI classification methods; predictive modeling that uses both real-time and historical data to forecast future health conditions; and the integration of external environmental factors to enhance predictive accuracy.

“A digital twin of your body would alert your doctor to a possible health risk in advance; if that risk became an emergency an ER doctor would be able to look at your digital twin before you are in the operating room, speeding up the process and allowing them to focus on life–saving care and not diagnosis,” says Diana, who has served in various executive roles during his career. “When we expand that potential to digital twins of places, a truly smart city would have a complete digital twin that its administrators use to plan new construction, optimize resources, and prepare for possible disasters. In a world where everything has a twin, humans will live longer, healthier, safer, more productive lives.”